Kiara Guley wants to be a cosmetologist when she graduates high school. But like many of her classmates at Palestine High School in Southeast Texas, she has a plan B: become a prison guard.

In the face of a severe staffing shortage, the Texas Department of Criminal Justice has turned its focus to recruiting high school students like Guley. She is one of several thousand students enrolled in a career and technical education course called “Correctional Services,” which prepares Texas high schoolers to work in the state’s sprawling and critically understaffed prison system.

Currently, more than 27% of corrections positions in Texas prisons are vacant. And in rural Anderson County where Guley lives, the situation is much more extreme. Over 910 Correctional Officer positions are unfilled across the county’s four prisons, a vacancy rate of 48.6%.

So the prison department has hired a recruiter to develop relationships with the hundreds of high school training programs across the state, hoping to make it easy and attractive for graduates ages 18 and older to become corrections officers. The agency “is exploring the option of establishing a pipeline for high school” students to become employees, Director of Communications Amanda Hernandez wrote in an email.

The pipeline Hernandez described is very different from the well-documented “school-to-prison pipeline” that puts youth in contact with the criminal justice system at an early age. Instead, the agency is on its way to formalizing a second “school-to-prison pipeline,” this time from high school student to prison guard. This new pipeline may have an outsized effect on students in Texas’ rural “prison towns”’ like Palestine, where prisons are some of the primary employers.

‘A Massive Movement’

The Texas agency’s new effort to work with high school programs is an approach that prison systems and police departments across the country are adopting as they try to find and keep employees, said Thomas Washburn, the executive director of the Law and Public Safety Education Network, a Georgia-based nonprofit organization that supports criminal justice programs in high schools.

“It’s a massive movement,” Washburn said. “Career and technical education programs are absolutely one of the solutions.” The group says 3,500 law and public safety education programs serve hundreds of thousands of students nationwide.

But Washburn said he has some misgivings when it comes to encouraging young people to become corrections officers. “I don’t know how to phrase this in a good way,” he said. “Corrections is a job whose challenges outweigh its benefits. It’s not a great career.”

Researchers have linked working in a prison to high rates of mental and physical health problems, including depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, substance abuse, and suicide.

But, Washburn said, “when it’s paying 40% better than anything else in your community, it is a viable option.”

In Texas, guards make between $42,000 and $51,000 a year, depending on experience, and are getting a 5% pay raise effective July 1, 2023. The officers earn an average of $8,000 a year in overtime, the agency says. In Anderson County, the average per capita income is $20,543, according to the United States Census Bureau.

“We don’t have a hiring problem, we have a retention problem,” said Benny Kinsey, the director of recruitment and retention at the Texas Department of Criminal Justice. Kinsey said the agency hires between 8,000-10,000 new corrections officers every year. But with an officer turnover rate of nearly 45%, the prisons struggle to keep positions filled.

“A lot of that comes down to the nature of the work,” Kinsey said.

While expanding the applicant pool and getting kids interested in corrections may help alleviate the staffing shortage, Washburn says it won’t be enough to address the underlying problem.

“As a teacher, I had a very difficult time steering kids in that direction,” Washburn said. “You almost feel like you’re somehow liable for suggesting that as a career.”

But the intention of the agency’s new outreach efforts to Texas schools’ criminal justice programs is to do exactly that.

The Prison System ‘Is What Defines Us’

Eighty miles down the road from Palestine is Huntsville, Texas’ most famous prison town. Huntsville is home to seven state prisons and the headquarters of the Texas Department of Criminal Justice. Prison-related attractions, like the Huntsville Prison Museum, draw tens of thousands of visitors a year. The museum’s collection includes manacles used to bind chain gangs, weapons carried by guards from 1848 through the present, and a gift shop selling T-shirts and handmade leather gun holsters. The electric chair known as Old Sparky, which the state used to execute 361 prisoners from 1923 to 1964, is also on display.

In Huntsville, “Everyone knows someone who is a corrections officer,” said Jordan Huebner, who went to Huntsville High School and now leads the criminal justice program there. “If it’s not your parents, it’s one of your friend’s parents. ”

The local school district and Sam Houston State University are also major local employers. But for students who want to stay in rural Walker County, in the Piney Woods of East Texas, the Department of Criminal Justice is “going to be your best option,” Huebner said, adding that at least 10% of her students will work in corrections in their lifetimes.

Texas is one of an increasing number of states where the minimum age to work in a prison is 18. Corrections “is a big pathway that we’re showcasing to the students since that is something that they can go and do as soon as they graduate from high school,” Huebner said.

The prison system “is what defines us,” said Ryann Kaaa-Bauer, a former police officer and one of the teachers at Huntsville High’s training program. The school has a set of dummies and batons to train students in use-of-force, as well as a collection of mock weapons and utility belts modeled after those carried by police officers.

The students’ favorite activity? “Oh my gosh, the students love handcuffs,” Kaaa-Bauer said. “And I mean that in the most positive and educational way possible.”

Corrections students must “demonstrate self-defense and defensive tactics such as ready stance and escort positions, strikes, kicks, punches, handcuffing, and searching,” according to state guidelines. Other topics of study include the mundane day-to-day tasks it takes to run a prison (efficient food service, good communication and organizational skills) and responding appropriately during “hostile situations.”

The corrections course taught at Huntsville includes units on prison intake procedures, searches and shakedowns, offender rights and services, and prison gangs, said Huebner and Kaaa-Bauer. Last school year, the program facilitated three prison tours and a trip to the Huntsville prison museum for a final exam in the form of a scavenger hunt.

Pathway to Criminal Justice Careers

In 2023, states will receive $1.4 billion in annual federal funding to support career and technical education programs across 16 career clusters, which include a variety of fields ranging from law enforcement and agriculture to information technology and health science.

Law and Public Safety programs can include classes on a number of related topics, from law enforcement, corrections, forensic science, and criminal investigation to legal systems and firefighting. In Texas, the curriculum standards are set by the Texas Education Agency, though teachers are free to use additional resources and materials.

Back in Palestine, Texas, many students signed up for the program because they were interested in criminal justice careers like police officer, lawyer, or criminal psychologist. Although none of the students interviewed at Palestine High School identified working in corrections as their main goal, a number of them thought becoming a prison guard would be a sensible second choice.

Fourteen-year-old Ruben Vasquez hopes to eventually work for the FBI or CIA. But if those plans don’t materialize, he also sees corrections as a possible alternative. “I’ve always wanted to go to college, but if that’s on hold I would definitely think about corrections, just to get experience,” he said.

A Heavy Toll

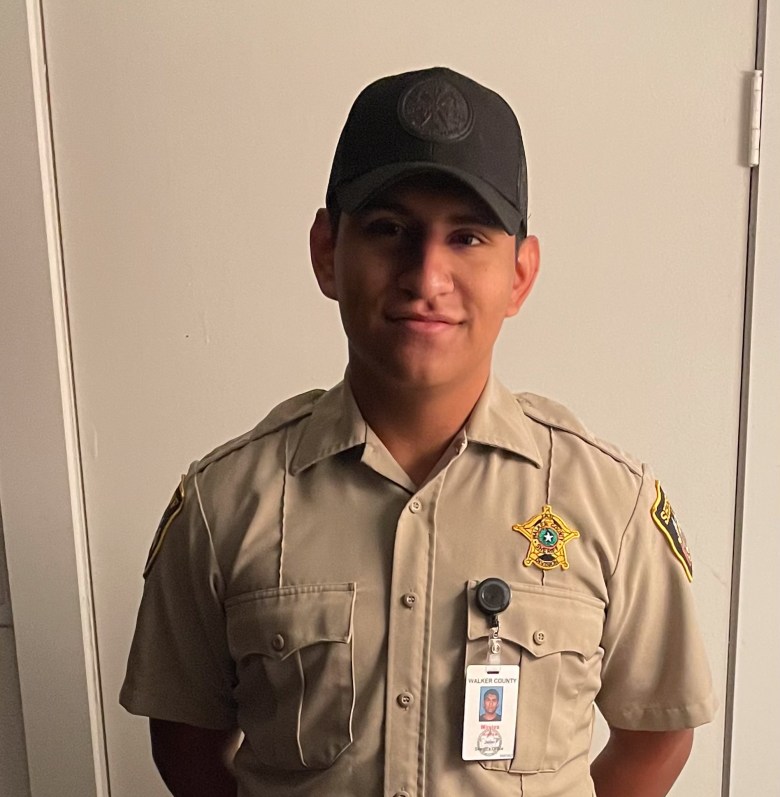

Andrew Mireles graduated from Huntsville High School’s criminal justice program in 2021, and applied for a position at the Walker County jail when he was 18. He attributes his decision to work in the jail to a sheriff’s deputy who came to speak to his class.

But after working in the Walker County jail for a year, Mireles decided he’d had enough. He plans to serve in the army for four years, and then return to the field of criminal justice. But he doesn’t want to work in a jail or prison again.

“After a while, I started to dread it,” he said in an interview with the Daily Yonder. “You don’t want to go there. You’re working 12 hours and it’s just very depressing.”

He said he enjoyed the first few months of the work, but that it began to take a mental toll. So he started taking measures to separate his work life from his home life.

“I have a plant by my front door. And after work I would rub my fingers on that plant and leave all my feelings about work on one leaf. And when I came home to my son and family I did not talk about work,” he said.

The next morning, he would rub the same leaf again to mentally prepare himself to go back to the jail.

“Corrections, it makes or breaks you,” he said. “It shows you if this is the career you want, and it’s not for the faint of heart.”

This article was published in partnership with The Marshall Project. It was produced with support from the Education Writers Association Reporting Fellowship program.