The Road to Blair Mountain: Saving a Mine Wars Battlefield From King Coal.

By Charles B. Keeney

West Virginia University Press

+++

Have you ever thought that our whole nation is West Virginia? Me neither until I read The Road to Blair Mountain: Saving a Mine Wars Battlefield From King Coal by Charles B. Keeney. Stick with me; this will take some explaining.

In popular lore, West Virginia is a one-dimensional piece of mountain territory dominated mostly by a single industry and ruled by King Coal. That may sound highly unusual until you ask, “Well, what is California except a piece of territory dominated by King Tech? And Missouri — all the way to western Iowa and western Kansas — some flat land ruled by King Ag?” Hold that thought that Mark Zuckerberg is really a coal operator.

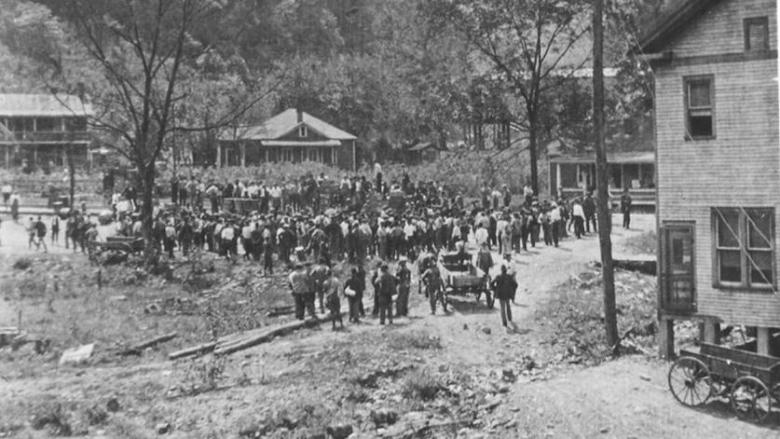

The Battle of Blair Mountain in Logan County, West Virginia, in 1921 was the largest battle on our national soil since the Civil War. For five days in September, 10,000 or so coal miners, led by Charles Francis Keeney and Bill Blizzard, faced off with 3,000 or so coal company guards, the local sheriff and 300 deputies, and a notorious private police force, Baldwin-Felts Detective Agency. The miners had their hunting rifles. The company guards had machine guns and were dug in on trenches high on the mountain.

Before the miners — deemed “Red Necks” from the bandanas they wore — eventually surrendered to the U.S. Army, an estimated 100 people had been killed, a million shells had been fired, and poison gas and bombs left over from World War I had been dropped on the battlefield by airplane. Some pretty big heavyweights, including President Warren Harding and General Billy Mitchell, the founding father of the U.S. Air Force, got involved.

If you’ve never heard of this battle, often described as “Labor’s Gettysburg” for its significance in labor history, don’t feel bad. Neither had the author of The Road to Blair Mountain, the great-grandson of march leader Charles Francis Keeney until he finally wrangled a bit of family history from his reluctant kin. The coal industry made sure the battle was never mentioned in the required state history courses in secondary schools, and until recently the battle didn’t come up in college courses either.

Hidden history bothers Charles Keeney tremendously. He happens to hold a doctorate in history and teaches the subject in a state community college in southern West Virginia. What makes this book — a combination history and memoir — so fascinating is that Keeney is one of the main actors in saving the historic battlefield from being devastated by mountaintop removal coal mining, one of the most destructive methods ever devised to extract fossil fuel from mountains.

I hold a degree in history and do not associate history with unexpected endings and certainly not often with adventure and excitement. We all know the little guy wins only when he manages to shoot from the highest hill or somehow to find a rich ally willing to drain its treasury to defeat a common enemy. (That would be the French in the American Revolution). Keeney makes the battles with the agencies and coal companies suspenseful to the very end.

The author and the little band of Friends of Blair Mountain defy the historical norms. They do not have a treasury (former Congressman Ken Heckler saves the day on a big march day by donating $500 for gas), an attorney, a public relations agent, any full-time staff, or a guidebook on how David can defeat Goliath when the giant has a thousand heads that have to be hit with a slingshot. This is where Keeney makes a real contribution with the book: He suspects we all have a Blair Mountain that needs to be protected from a King Somebody or King Something. In his words:

“Grassroots activists and indigenous people, often in rural areas, find themselves facing enormous odds when protecting sacred landscapes against the financial and political might of major extraction and agricultural industries. Such individuals and groups may find valuable lessons in this book….My theory is that people from different regions of America will find more similarities than differences in the local politics, economic problems, and social issues described in this book.”

In March 2009, the 1,700 or so acres of Blair Mountain were placed on the National Register of Historic Places, set to be protected from mining forever. In December of the same year, it was mysteriously delisted. Three coal companies had been permitted to do mountain top removal mining adjacent to the battlefield and the National Guard was cooperating with the coal companies and state agencies to place a national jump base — part of the global battle against terrorism — on the stripmine benches. The coal companies were cooperating with the National Guard because of “God and country,” one company executive said.

In 2011 Keeney was named president of the Friends of Blair Mountain and realized the little group of locals, labor historians, environmentalists, and assorted others, including some outsiders who felt civil disobedience was the best strategy to protect the mountain, did not have a common strategy to overcome the odds against them. Many of the supporters insisted the battle had to be to abolish mountaintop removal in the state, not to single out Blair Mountain for special protections.

Keeney is a local and knows that the United Mine Workers support mountaintop removal because its members operate the dozers and giant shovels. He also knows “tree hugger” is the most damning and dangerous epitaph one can acquire in the southern coalfields, where the coal operators allege there is a “war on coal” and bumper stickers with “friend of coal” dot the bumpers and rear windows of pickup trucks. He persuaded the group to adopt a three-prong, very focused strategy of saving Blair Mountain.

The tenets of the strategy were:

- Take control of the public narrative and aim to create support among the local population.

- Learn the system of laws, regulations, and agencies and figure out how to maneuver inside those bureaucracies.

- And finally, get in the room with all the players and present solutions on which all can agree.

The shorthand for the strategy became “History, Labor, Culture.”

The group knew that most victories from social protest in this country are won with numbers, large groups of people mobilizing for change. They also knew rural areas like theirs don’t have numbers. And they also knew the social fabric of small towns and rural areas often means any struggle could mean the loss of friends or jobs. As the author puts it:

“The (coal) industry has held sway over the state for so long that to go against the coal industry in any way is to break a social norm. A feisty inspector who does not get with the program could be prodded in a variety of ways. Perhaps the state suddenly audits his family. If bad weather causes the water pipelines to break, perhaps his house is the last one in the holler to get repairs. Perhaps an inspector writes up violations and suddenly his daughter does not make the cheerleading squad, or his son is benched on the little league baseball team, or his wife gets shunned at local church events. When a baseball coach is also a mine superintendent, the cheerleading coach is the wife of a surface miner, and each member of the local school board is a stockholder in the companies, pressure can be applied in a variety of small, nearly untraceable ways. No phone calls need to be made. No orders need to be issued. It just happens.”

Many of those things happened to members of Friends of Blair Mountain. They are threatened, they are followed, they suspect their email and phone records are tapped, and state agencies regularly ignore their letters and emails. Keeney’s computer was hacked six times. The fight drags on until 2019. Maintaining resolve and members is a daunting task. Keeney quotes Muhammad Ali: “It isn’t the mountains ahead to climb that wear you out; it’s the pebble in your shoe.” He adds, “We endeavored to be the pebble in King Coal’s shoe.”

The group managed to find a couple of attorneys who would work for nothing more than gas money. Environmental organizations like the Sierra Club joined the fight and brought aboard experienced attorneys and media strategists. Federal courts in the state ruled against them, and in turn they were overturned eventually by appeals courts distant from the state and local politics. Volunteer archeologists and labor historians offered testimony and volunteered time that kept the battle alive at the many agencies, state and federal, that had to be dealt with. Things looked pretty bright at one point, and then a coal operator was elected governor, a new president pledged to revive coal and strip agencies of regulatory power, and the state Legislature went Republican.

Just when it looked like the children of darkness were in charge everywhere, the coal companies threatening Blair Mountain start going bankrupt; Don Blankenship, a powerful coal executive, goes to prison for violations related to a deep mine disaster; and the National Guard trims back its plans for the jump base. Best of all, the state determined, in conjunction with the federal courts, that the Blair Mountain Battlefield belonged on the National Register of Historic Places all along. It is now protected from coal mining but maybe not from drilling for natural gas. The battleground is now becoming sufficiently well known that any kind of drilling is very unlikely.

During the time that this battle for Blair Mountain was going on, the group was working with others in southern West Virginia to correct the problem that few people knew little about the long history of mine wars and the struggle for decent pay and safe working conditions in the mines. They established the West Virginia Mine Wars Museum in another historic little town, Matewan. It has become a sensation, attracting attention from students, scholars, miners, and tourists from all over the country. Keeney terms it a weapon in destroying “the Mind Guard System” that kept West Virginians from knowing the Mine Wars and state labor history.

Here’s the museum website. There is one little piece of history in the museum worth special notice. The coal companies used to pay miners in “scrip” instead of dollars. Scrip could only be used at the company store and usually had a company logo and the denomination of the coin printed on it. One scrip in the museum testifies to the total control companies once had. It says, “Good for one loaf bread.”

The book ends with a very long list of lessons learned from the struggles of the Friends of Blair Mountain. Some examples:

- Accomplishing goals will be harder than you think and take longer than you estimate.

- Pragmatism is more crucial to success than idealism.

- Wherever possible, treat those who oppose you as adversaries, but not as enemies.

- Constantly discuss strategy and document everything.

And the final and best advice that Keeney hopes his readers will take action on is “find your own Blair Mountain.” He does a good job of connecting the conditions in West Virginia coalfields to the major problems, like climate change, corporate power, and corrupt or incompetent politicians, that plague the nation and world. He doesn’t call Mark Zuckerberg a coal operator. That was me, but you get the point. Keeney wants a whole nation of Red Necks. Just like those striking West Virginia teachers and their red bandanas that inspired teachers all across the nation in 2018.

Jim Branscome is a retired managing director of Standard & Poor’s and a former journalist whose articles have appeared in the Washington Post, New York Times, Business Week, and Mountain Eagle of Whitesburg, Kentucky. He was a staff member in 1969-71 at the Appalachian Regional Commission, a lobbyist for Save Our Kentucky in Frankfort, and a staff member of the Appalachian Project at the Highlander Research and Education Center in New Market, Tennessee. He was born in Hillsville, Virginia, and is a graduate of Berea College in Kentucky.