Editor’s Note: This interview first appeared in Path Finders, an email newsletter from the Daily Yonder. Each week, Path Finders features a Q&A with a rural thinker, creator, or doer. Like what you see here? You can join the mailing list at the bottom of this article and receive more conversations like this in your inbox each week.

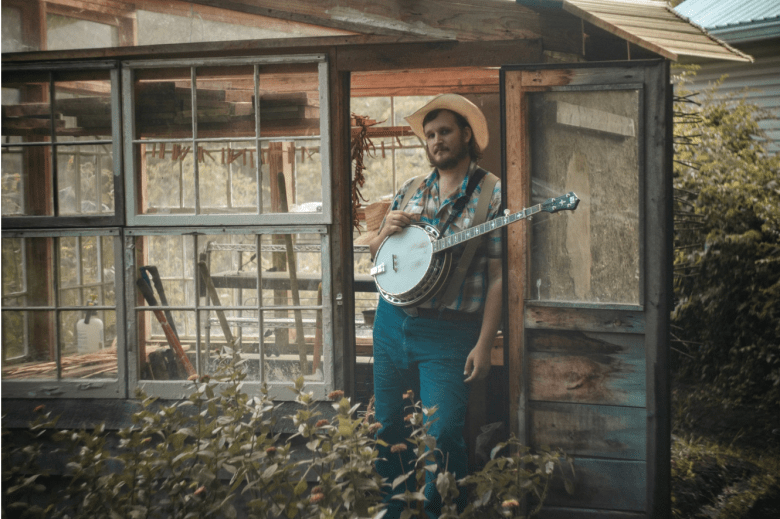

Willi Carlisle is an overeducated folk singer who lives in Arkansas’s Ozarks, and sometimes a van. A couple of weeks ago a friend of mine from home saw that Carlisle was coming to my college town, and told me I needed to get a ticket. My friend has good taste – by which I mean taste very similar to mine, so I was expecting to enjoy the music. I wasn’t expecting an evening of elaborate drawings of people and vehicles the singer loves, audio recordings from his life (including a square dance, a moment of extreme lovesickness, and a traffic stop over an expired sticker), or rambling populist musings. But I’m glad that’s exactly what I got.

Since then, I’ve been able to ask Carlisle some questions. Enjoy our conversation about teasing his audience, punk-folk overlap, and the uncomfortable realities of #vanlife, below.

Olivia Weeks, The Daily Yonder: There’s a real self-awareness to your shows. I saw you at Club Passim in Harvard Square, where lefty folk singers are a dime a dozen and you were far — in more ways than one — from your home in the Ozarks. Afterward I wondered, do you change your shows up from location to location?

Willi Carlisle: I’m so glad to be self-aware, and so glad that it shows! I absolutely change up my shows depending on the audience. Ya think I’m gonna play in Harvard Square and not tease lefty academics? That’d be a shame! I pretty much tease every audience at least a little bit. I realize there’s an aspect of “performing authenticity” that makes folks think code-switching is somehow dishonest, but I don’t really buy into that. Lots of us have HAD to code-switch.

I cherish my ability to enter a lot of spaces and learn a lot of crafts. I want to be a good steward to that privilege and access, so I seek out multiplicity and contradiction. Folk music (as a craft) is pluralistic. Why shouldn’t that be part of what we do? I like what Groucho Marx said: “I wouldn’t want to be a part of any club that would have me as a member.” I count lefty folksingers as one of those clubs. Better yet, Woody Guthrie: “a folksinger’s job is to comfort disturbed people and disturb comfortable people.”

If I appeared to be an apologist for right-leaning country folks during my show in Harvard Square, you should see my far-left apologist bit in small-town Arkansas! I reject “us-vs-them” framing in general. It’s a convenient, xenophobic fiction in a land of inequality, partisanship, and impending apocalypse. We need each other far more than we know, and I’m lucky to know a lot of people.

DY: Is there a freedom to playing for people who seem more politically aligned with you on the surface, or does it feel like your job to explain the country people you love to them? How do you think about your audience, and which parts of you they might be more or less amenable to?

WC: I think I’d actually simplify the first question! Yes, there is a freedom in singing for everyone. It’s a freedom everyone deserves: to be yourself and to be useful. When I think about who’s amenable to what, I think of it as regional codes of decency that can be disrupted. I dunno. I’ve showed up queer to every show I’ve ever played. Does that make them “queer shows”? Am I sexless if I don’t talk about sex with my grandmother? Does talking about queerness in a queer space make me “more comfortable” or is this merely a modality I understand? Bigots exist, but they’re wrong, hurting themselves, insular, lonely, stupid. Me? I’m lucky! I’m comfy. I’m free. I’m a clown with a guitar. I think about my audience and I love them with ardor and discomfort. I hope they feel the same.

DY: On your website you’re described as “a product of the punk to folk music pipeline that’s long fueled frustrated young men looking to resist.” I wanna hear more about that pipeline – what was the punk Willi of your youth resisting and how’d he wind up so enamored with folk music?

WC: When I was developing some sense of who I wanted to be, it struck me that Monsanto’s policies towards migrant labor and corporate profits pissed me off. I was pissed off that the Maytag plant closed in the small town I lived in. Hell, I was pissed that I didn’t know how to talk about being queer, pissed that people didn’t like me, pissed. Teenager pissed. “The World is Unfair” pissed. I loved “Paradise Lost” and “The Twilight of the Idols” and “The Fountainhead.” I was a casual self-harmer, a dungeons and dragons nerd, a heavy drinker, and was probably difficult to be around.

Then, when college roommates introduced me to punk music, it was the perfect blend of calculated performance and terrifying risk. I loved it: to play poorly and sound amazing excites me, and a small renaissance was beginning at that time in that little Illinois town as bar flies and record collectors came together with angry, funny music. Me and my friends made a shitty band and joined them. We were a “scene.” It remains one of the coolest things I’ve ever done, and one of the most freeing. I wish all music communities were this way: you suck, but it’s honest, and your peers come up and say: “Wow! Great job!”

I found folk music through these folks — they introduced me to John Prine, Leadbelly, Ralph Stanley, and Skip James, and I found that I’d been hearing these kinda songs all along, that there were a lot of stories in my family about seeing these performers and listening to this old music. I bought a guitar and a banjo right away. I never looked back. It made me endlessly happy. Add square dances and oldtime music? Heaven.

DY: Tell me more about the song Vanlife, and its inspiration. What was your living situation at the time when #vanlife started trending? How’d you feel about it? I love the chorus of that song, where you say “it’s a fine line between havin’ to and choosin’ it,” and I wonder what you’ve been thinking about the “choices” facing younger (or artistic or otherwise economically precarious) people trying to figure out where and how to live.

WC: I’m no expert, but driving around the country one can see the epidemic of housing insecurity and homelessness by the tents and camps in every mid-size city.

As a young punk traveling, going to school, and working, I saw a bit of how the housing crisis in 2008 affected people. Construction and painting jobs were full of downwardly mobile folks. By the time I made it to Arkansas, friends of mine were at Occupy Wall Street and I was teaching at the University of Arkansas. I remember wondering (in my dirty jeans and unprepped classes) why I wasn’t out there, why I’d missed such a cultural turning point.

As I began to make a career out of music I realized the only viable option was not paying rent, was living on couches, spare bedrooms, and in the van while I got my work together. I played in nursing homes, DIY venues, breweries. It was something I was already fairly used to, and the indignities of that kinda “fashionable” vanlife were pretty manageable compared to most of the folks I’d met whose lives were devastated by the busts and income inequality that defines this generation. That hard-traveling lifestyle (about 3-4 years of it) informed that “it’s a fine line between havin’ to and choosin’ it,” because a lot of folks never had a choice, a lot of folks were in-between jobs, temporarily embarrassed, or the like.

For artists? I think I recommend it. It’ll give you a chip on your shoulder, keep your nose in the world and away from pure fantasy. The nostalgia of music and art (especially if you’re overeducated, like me) is dangerous, and I think I’d live in a book if I could. I’m really grateful for the fine line in my own life, because it solidified my belief that everyone deserves dignity, and that we need that more than aircraft carriers.

DY: Have you had any good ideas, lately, about what we should do with ourselves?

WC: I admit I have no idea. I’m not even an angry person anymore, so I’m not sure what’ll motivate me. It might have to be affection, if not anger. Leave me a little love, wont you, friends?

This interview first appeared in Path Finders, a weekly email newsletter from the Daily Yonder. Each Monday, Path Finders features a Q&A with a rural thinker, creator, or doer. Join the mailing list today, to have these illuminating conversations delivered straight to your inbox.